(Originally published on October 30, 2015)

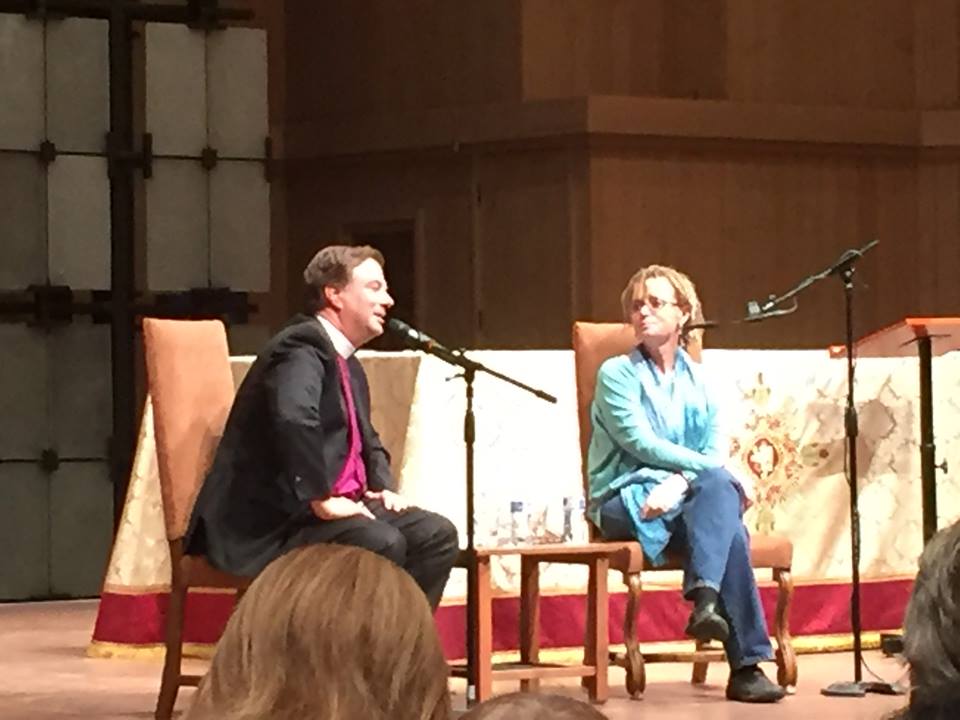

This weekend I’m attending the conference of Episcopal Recovery Ministries here in Seattle. The first day culminated in a talk and book-signing by Anne Lamott, who had many interesting things to say. She was interviewed by our bishop, Greg Rickel, and one of his questions was about “the church, capital C,” as he put it. He wanted to know what she thought about the Church, about what ails it, what its dilemmas might be. Lamott straightforwardly responded—and she’s someone who loves her church—by saying, “The Church is alcoholic.”

She explained her answer, talking about how the Church is made up of folk who are addicted, not just to substances but to control, or to a fantasy of blissed-out community, or to a projected self that’s not angry or scared or sad (even though we pulse with those raw, human emotions, and even though Jesus did too). The Church is full of anxious people trying to control the universe around us, trying to project confidence and serenity when inside most of us are pretty messy.

This got me thinking and feeling in lots of directions, and one of them was a principle our consultants hold to in their work with congregations: the client is the agent of change. This is a dry-sounding concept that is actually pretty insightful and powerful. When our consultants come to your church to help you plan your year, resolve a conflict, manage a priest transition, or learn about personality type and apply it to your group work, the consultants can’t make the changes. They can’t do the work of the congregation.

But oh, how I as a consultant would love to do just that!

Our work as consultants—and your work as lay and clergy leaders in your congregations—is to avoid that kind of over-functioning, and cultivate instead a skillful, human presence that can assist the larger group in the work that God has invited them to do. We can facilitate a meeting effectively, teach development tools that clarify and focus their work, suggest practical options for them to consider, and model for them a conscious, authentic leadership presence that can help them be the healthy and sustainable congregation they truly are. But we can’t do their work, any more than we can be the congregation itself.

One of the ways I approach this as a consultant is to begin by finding something to love or appreciate about the congregation, my client. In a sense, I fall in love with them. That sounds like I’m going in the wrong direction—won’t I become co-dependent and controlling if I have an emotional relationship with them?! But it’s not like that. I get quiet. I get reflective and try to listen to my client. I listen for strengths, gifts. When they reveal weaknesses or problems, I hear those too, but look for ways they’ve been bearing up under the strain. And I remember all of that whenever I’m tempted to take over. I don’t need to take over, because I know they’ve got strength and skill. And I know God is with them. And I know I’m not God.

And that’s a relief for everyone, because if I’m not God, I can be their consultant, their thinking, feeling, relating, fallible, human consultant, who has a few helpful ideas, and a willingness to walk alongside them for a while.

Anne Lamott was right about the Church and its addictions and anxieties. But she also understands and trusts God’s presence in all of this, and the authentic hope we can cultivate within ourselves that lovely, life-saving things can happen in our communities of faith.

—Stephen Crippen